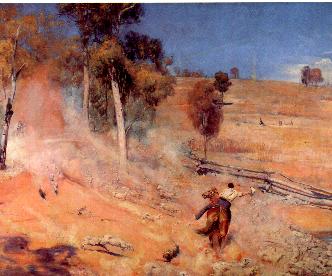

Down on His Luck

(1889) by Fred McCubbin

Bush Ethos as defined by Russel Ward 13

Following the opening of the Australian inland by explorers, men from the cities decided to make their living in the bush. Living in an open, harsh and lonely environment, was a different experience from that of England. It was believed that this experience gave birth to a special breed of men: hard working, self-sufficient, individualistic and freedom loving.

The Australian historian Russel Ward wrote a provocative essay entitled The Australian Legend. In this essay, Ward traced the origins of the Australian type from the convict, the itinerant bush worker, bushranger14 gold digger and Anzac soldier. Russel Ward was the undisputed authority on the subject of Australian identity until the 1980s.

In The Australian Legend, Ward argues that when Australians turned away from Britain in search of something uniquely Australian, and in particular when artists sought inspiration from distinctively Australian sources, the Bush15 was perfect. The Bush ethos was distinctive. Drawing upon historical documents, literature and folk ballads, Ward traced the process by which a distinctive bush and working ethos spread throughout Australian society to influence the manners and morals of the whole population. In the foreword to his book Ward sums up the purpose of his essay:

This book attempts to trace the historical origins and development of the Australian legend or national mystique. It argues that a specifically Australian outlook grew up first and most clearly among the Bush workers in the Australian pastoral industry, and that this group has had an influence, completely disproportionate to its numerical and economic strength, on the attitudes of the whole Australian community.16

Russel Ward, in the foreword of the 1966 edition of his book, went on to explain this a little further:

The Australian Legend does not purport to be a history of Australia or even primarily an explanation of what most Australians are like and how they came to be that way. It does, as the title suggests, try to trace and explain the development of the Australian self-image of the often romanticized and exaggerated stereotype in men's minds of what the typical not the average, Australian likes (or in some cases dislikes) to believe he is like.17

Down on His Luck

(1889) by Fred McCubbin

National character, argues Ward

...is not, something inherited; nor is it, on the other hand, entirely a figment of the imagination

of poets, publicists and other feckless dreamers. It is rather a people's idea of

itself and this stereotype, though often absurdly romanticized and exaggerated, is always

connected with reality in two ways. It springs largely from a people's past

experiences, and it often modifies current events by colouring men's ideas of how

they ought "typically" to behave.18

In Ward's view, the mythical bushman is commonly regarded as ...a practical man, rough and ready in his manners, and

quick to decry any appearance of affectation in others. He is a great improviser, ever willing

to "have a go" at anything, but willing too to be content with a task done in a

way that is "near enough". Though capable of great exertion in an emergency, he

normally feels no impulse to work hard without good cause. He swears hard and

consistently, gambles heavily and often, and drinks deeply on occasion. [H]e is usually

taciturn rather than talkative, one who endures stoically rather than one who acts busily.

He is a "hard case", sceptical about the value of religion, and of intellectual and cultural

pursuits generally. He believes that Jack is not only as good as his master but, at least in

principle, probably a good deal better, and so he is a great "knocker" of

eminent people unless, as in the case of his sporting heroes, they are distinguished by

physical prowess. He is a fiercely independent person who hates officiousness and

authority, especially when these qualities are embodied in military officers and

policemen. Yet he is very hospitable and, above all, will stick to his mates through thick

and thin, even if he thinks they may be in the wrong.19

These characteristics were widely attributed to the bushmen of the

nineteenth century such as the outback employees, the semi-nomadic drovers, shepherds, shearers,

bullock drivers, stockmen, boundary-riders, station-hands and others in the pastoral

industries. Material conditions of life in the Bush were so harsh that in order to survive

they had not only to be self-reliant but also to rely on each other, which explains

mateship20.

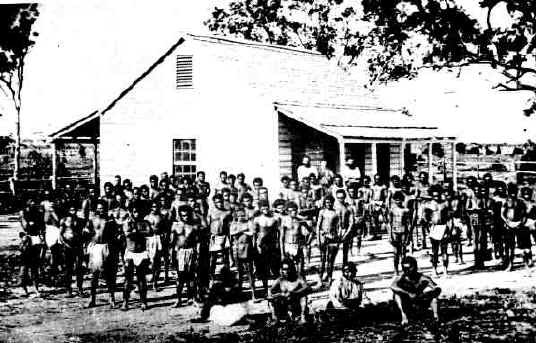

Aborigines never appeared as more than marginal figures in The

Australian Legend.The essence of the Legend, it was argued, was the struggle of "man"

with the land. Sacrifice and suffering were considered

essential components of making the land. The importance of the legend is that the Australian

has earned the right to possess the land. The very use of

terms like "pioneers" and "land explorers" as applied to white

settlers negate the existence and role of the Aborigines, as the concept of Terra

Nullius seemed to indicate. The white settlement of the continent is part of

the image of the triumphant spread of civilization around the globe. In this version of

nation-building the heroism and suffering of the whites is to be celebrated and the

Aborigines are considered "primitive" and incapable of reaching the level of the

white civilization. The beginning of Australia as a penal colony could be compensated by

submitting an outstanding national type.

Not only did the "bush worker" contribute to the vitality of the nation's

economic growth but he had all the qualities needed for doing the "job":

self-reliance, virility and a sense of loyalty towards his friends. In the context of the

renewed nationalism which accompanied the Federation of the Commonwealth of Australia in

190121 the bush worker became the first genuine "Australian type" that the

population could be proud of. Official historians of the first half of the twentieth century

tried to avoid linking the convict character (with its collectivist anti-authoritarian

morality and need of physical endurance) to the new modern Australian. Ward's essay was, therefore, controversial because, for first time, he traced

the modern Australian identity back to the convicts (he refers to them in chapter

8 as "The Founding Fathers"). Ward argued that mateship could only be explained by taking

the convict experience as the starting point for the construction of the Australian

character: England has her Angles, Saxon and Jutes, and America her

Pilgrim Fathers.... But we Australians often display a certain queasiness in

recalling our founding fathers. Even today many prefer not to remember that for nearly

the first half-century of its existence White Australia was, primarily, an extensive gaol.

Yet recognition of this fact is basic to any understanding of social mores in the

early period when the Australian tradition was forming.22

The fact that Ward dared to state that the modern Australian owes

much to his convict ancestors showed a newly acquired confidence in the self-reliant

nature of the white Australian population, often pinned down as a second-rate nation

because of its criminal ancestors. Robert Hughes, among other historians,

followed in Ward's footsteps. His bestseller The Fatal Shore, published in

1987, dealt exclusively on the convict history and its importance in shaping the Australian

character. In the introduction he wrote about the resistance of

Australians to acknowledge their "convict past": An unstated bias rooted deep in Australian life seemed to

wish that "real" Australian history had begun with Australian respectability - with

the flood of money from gold and wool, the opening of the continent, the creation of the

Australian middle-class. Beyond the bright diorama of Australia Felix lurked the convicts,

some 160,000 of them (...) on the feelings and experiences of these men and women, little

was written. They were statistics, absences and finally embarrassments.23

Despite what we can now identify as obvious flaws (such as a lack of recognition

of both Aborigines and women as nation-builders) Ward's The

Australian Legend was an indispensible reference book for historians and teachers throughout

the country since its publication in the late 1950s. Australia was colonized by the British and virtually all its

institutions - governmental, administrative, judicial, financial, educational, religious

and cultural - came from the British with only minor adaptations. But unlike Britain,

nineteenth century Australian egalitarianism involved a belief in a

classless society where wealth is evenly distributed and where all are free to socialize.

People were to be judged on their merits and not on social background; deference was neither

expected nor given. The Victorian gold-fields of the 1850s was the place where the

egalitarianism ethos became fixed once and for all as an Australian feature. The

accessibility of great wealth through luck and the absence of an aristocracy had a profound

impact on social relations. The revolt by a group of miners from all social backgrounds against

exorbitant mining licenses at Eureka was just one example of this spirit24.

The belief that class divisions were not rigid and that all citizens

had the same rights led to egalitarianism and to a notion of political equality. Australia along

with New Zealand led the world in reform based on the Chartists' agenda including suffrage

25, the secret ballot 26 and the franchise to women

27. Australian egalitarianism insisted on

racial sameness, which involved the assertion that Australians were racially and

culturally the same. This explains the push for a democracy based on political equality.

Australian egalitarianism has not meant an individualist commitment to equality of

opportunity as it has been conceived in the United States. It has in Australia, involved a

collectivist approach which became apparent with the voting of laws, mentioned earlier, as

well as with the birth of a number of organizations28

in favor of an equal treatment for all. The pressure for equality carried with it an intolerance towards

"respectability" and "manners", a hostility towards authority, a talent for improvisation, and an

idealization of male comradeship in a country which for a long time had a population imbalance

of four males for one female. Such attitudes were shaped, in part, by a disproportionately

strong Irish influence in those transported to Australia and with them a distaste for

British middle-class authority and values. Historians, such as Russel Ward and Robert Hughes, have attempted to root

this egalitarian-mateship theme in the early convicts with echoes found in the bushmen and

pioneers, the bushrangers, the gold diggers, and in the Anzac soldiers'29

courage. It is true to say that they emphasized what seemed to them

valuable in the radical nationalist tradition, the demand for political, economic and

cultural independence - and down played what was ugly in that tradition.

30 But one must not forget that much of the Australian population was in

fact excluded from the ideal of egalitarianism. European definitions of race hierarchy

were used to exclude non-whites from the top of the human pyramid. This explains how

"egalitarianism" (the Australian way) and racism could co-exist until the 1970s. Women were also

actively excluded because mateship (a form of male companionship) was seen as the living

expression of Australian egalitarianism. In fact, for Ward, One important, though indirect result of the absence of women

was to generate the cult of mateship ... the tradition that a man should have his own

special "mate" with whom he shared money, goods, and even secret aspirations,

and for whom, even when in the wrong, he was prepared to make almost any sacrifice.

31 C.E.W Bean, for his part, insisted on the notions of fidelity and

loyalty implied in the term of Mateship by stating that, Once ... taken a man on his merits for a friend ...

[he places] absolute trust in you, absolute fidelity on his side.32

One can argue that mateship can be

found amongst the "working classes" around the world. Solidarity among workers against employers

is certainly not specific to Australian workers but it was believed to have special

qualities as it was claimed that it originated in the Australian bush

among free spirits who developed special characteristics of independence and silent

nobility.33 Many have argued that the male bonding which developed among the

pastoral workers of the nineteenth century was mainly due to a gender imbalance in

colonial rural Australia. For example, Ward gives the figure of a four to one excess of males

over females34 in rural New South Wales in

1841. In fact the absence of women was heavily encouraged by the squatters35

who asked for single men with no encumbrances ... for he does not wish to support, and

bring up other people's children.36

Employers in the country were then unwilling to provide rations for unproductive pregnant

or nursing women and children in their early teens. That the bush worker could not have a

family was a critical factor in shaping the ethos of the Bush. It helped forge the image

of the wild colonial boy, the free male spirit who enjoyed his

bachelorhood and avoided matrimony. Egalitarianism and mateship became parts of the Australian legend. It

became the workers' creed and ensured solidarity against employers. By acting

as the emotional backbone of the union movement, it played a critical role in gaining good

wages as well as good working conditions37 for the average worker.

Although mateship had a positive side it also had an

unattractive side. Mateship tended to include young white males and exclude women and

aborigines and can, as such, be seen as racist, ethnocentric and paternalistic - not very

egalitarian! Egalitarianism, the Australian way, was a white Anglo-Saxon male thing. Gallipoli and the ANZAC Legend (1915)

...The local imperialists, who believed that Australia

could only survive as a vassal of Great Britain, held that the solvent for the Birth Stain

was blood - as much of it as England needed for her wars38 The question that concerned many Australians after Federation39

(1901) was how it could gain a sense of national dignity, prove its worth and stop being referred

to as a "nation of criminals"? An opportunity to do this came in 1914 when Australia entered

World War I. Since 1908, when military conscription was introduced, all boys

aged 12 to 18 were drilled in military training for several weeks each year. School

children were told to be ready to sacrifice themselves for God and the King. Writer

Henry Lawson emphasized that it is in the supreme conflict (of war) that nations

are born.40 The outbreak of war in 1914 became a way for Australia to forge

an identity. The strength and vitality of a nation was judged by its fighting soldiers on the battlefield. On 25 April 1915, Australian and New Zealand troops landed on the

shores of Turkey to help push Turkey out of the Dardanelles to allow Russian ships access

to the Mediterranean Sea. They mistakenly landed at what is now known as Anzac Cove and

met with strong Turkish resistance from the high cliffs above. Under heavy gunfire, the

Anzac troops forced themselves onto the beach and made advances up the ridges. However, in

nine months of fighting they could not dislodge the Turks from their position. The military landing at Anzac Cove is the historical event from which

the myth of the Anzacs grew. Myth may be thought of as a "fantastic" story,

arising from a collective belief, which gives events and actions a particular meaning. But

a certain amount of "truth" is an essential element in myth making. The Anzac campaign happened only fourteen years after the

Federation of the Australian colonies into a nation in 1901. The timing here is

significant. The Anzac story, kept alive by war correspondent C.E.W Bean and contemporary

historians such as Ken Ingliss, Alistair Thompson and Patsy Adam Smith, crystallized many aspects

of assumed Australian qualities such as courage, patriotism, Bush values and the mateship of

Australian men in adversity. Australia waited in nervous anticipation during the first weeks of the

campaign wondering whether the troops had proven themselves on the world stage. Before

long, the British and Australian war correspondents, Ellis Ashmead Bartlett and C.E.W

Bean, told the world how magnificent the Australians were. The significance of this "glorious

defeat" is still impoertant today to many Australians even though its significance is lost on

many non-Australians. For example, from an American

edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica we read: Gallipoli was the scene of a determined Turkish resistance to the

Allied Force during the Dardanelles campaign of World War I, in which most of the town was

destroyed.41 From an Australian perspective though, the official war correspondent,

Charles W. Bean, who was the one of three journalists to witness the landing of the

British Empire troops at Anzac Cove declared: It was not merely that 7,600 Australians and nearly 2,500 New

Zealanders had been killed or mortally wounded there, and 24,000 more (19,000 Australians

and 5,000 New Zealanders) had been wounded, while fewer than 100 were prisoners. But the

standard set by the first companies at the first call - by the stretcher-bearers, the

medical officers, the staffs, the company leaders, the privates, the defaulters of the

water barges, the Light Horse at the Nek - this was already part of the tradition not only

of the Anzacs but of the Australian and New Zealand peoples. By dawn on December 20th

Anzac had faded into a dim blue line lost amid other hills on the horizons as the ships

took their human freight to Imbros, Lemnos and Egypt. But Anzac stood, and still stands,

for reckless valour in a good cause, for enterprize, resourcefulness, fidelity,

comradeship and endurance that will never own defeat.42

A Break Away

(1891) by Tom Roberts

Most of the soldiers showed great pride in themselves. Other characteristics surfaced which can be seen as less positive. A dislike of authority and the attitude of Jack is as good as his master were applied to the military police, particularly the British. As a result, brawls often broke out, with the Australian soldiers strong belief in egalitarianism putting them at odds with the British army. Whereas British officers were mainly drawn from the more privileged sections of British society, the Australian Army promoted soldiers according to their abilities. This often led to the Australian soldiers showing disrespect to the British officers (in, for example, an unwillingness to salute them).

Apparently the Legend is still alive and kicking as the article published in April 1993 by Nigel Adnum, a journalist for the magazine The Bulletin, clearly demonstrates. He visited the site of Gallipoli in Turkey, with several hundred other young Australians and New Zealanders in 1992 and gave an account of why the tradition still lives on,

I will never forget Gallipoli. I will never forget the sacrifice - and that it might have been me. I think I understand now about an historic point in Australia's development. In my fellow pilgrims I saw the Anzac spirit. The camaraderie, the respect for the fallen men, be they Anzac or Turkish, made me proud. There was no glorification of war but a deep understanding of how important it is that this should never happen again. I know now that on every Anzac Day I will remember all the unknown men and women who sacrificed themselves in the hope that others might live a more secure life. At the going down of the sun and in the morning, we will remember them.43

From Empire Colonies to Federation (1788-1901)After the War of Independence in America, Britain had to look elsewhere to transport her growing number of criminals44. With the arrival of the First Fleet of Captain Arthur Phillips in 1788, New South Wales became a penal colony for the British Empire. It goes without saying that the living conditions of those early years were appalling. They have been described in many books, the most famous recent one being The Fatal Shore45 by Robert Hughes.

Governor Lachlan Macquarie (1809-1821) was an important figure of colonial Australia. He arrived in New South Wales in December 1809 and while being firmly in control46 , he dedicated himself to improving the colony. He set up a building program, the Bank of New South Wales, the Orphans' Institution, a post office, a police force and expanded the school system. Despite the growing number of free settlers47, the colony of New South Wales remained basically a jail colony48 Hence Macquarie decided to reform the convicts by giving them the opportunity to become small farmers who could support themselves when they were released. The belief of Macquarie in the possible redemption of convicts through emancipation was an important one for Australian society as it helped soften the burden of Australia's convict past.

Governor-General Macquarrie (1810-1821)

The introduction of merino sheep by John Macarthur in 1797 was also an important historical decision which gave Australia its first viable industry49, allowing it, in the long run, to become self-sufficient50. The new industry also meant that more free settlers came to Australia, hoping to start a new life. Soon after the end of transportation around the 1850s, free settlers outnumbered convicts.

To fully develop its pastoral industry, the young colonies needed vast tracks of land and the Blue Mountains as well as the Great Dividing ranges were as many obstacles to achieve that aim. So from the 1810s to the late 1860s, land explorers set themselves to prospect and map the continent. Gregory Blaxland, Charles Wentworth and William Lawson were the first to find a way through the Blue Mountains in 1813, allowing a road to be built west of Sydney. The rest of the country was unlocked in the next sixty years by explorers such as Edward John Eyre and Charles Sturt. Some died during their journey (Burke and Wills) while others vanished without a trace in the vast Australian interior (Ludwig Leichhardt).

The land explorers were important to white Australia as they led to the impression that the Europeans had "discovered" the land for themselves. Pioneers of the bush settled throughout the country, pushing the Aborigines further away. The native population drastically declined due to new diseases, alcohol and violent conflicts51. The Aborigines were quickly dying out52 and it was hoped that white Australia would develop.

The discovery of gold in Victoria in the 1850s, was another major event in the development of the young nation. The massive immigration that followed and the prosperity Australia enjoyed at the end of the nineteenth century led Australians to consider independence as an achievable and desirable objective.With prosperity came the wish to attain independence. To gain self-government53, the colonies had to develop representative government54 and then responsible government.

The movement from "rule by the governor" to "parliamentary rule" was accomplished through several Acts from 1824 onwards. In 1827, free settlers demanded a parliament but the British Government refused. Transportation of convicts to the east coast ended in 1840, removing a major obstacle to representative government in the colonies. Around 1850 there was an increase in immigration. Three out of four people were free settlers. There was an increase in wealth as well, which led to further demands for parliamentary government and trial by jury. In 1850, the Australian Colonies Act was passed by the British Government. By 1890 all of the colonies had won self government (see table below).

Name of the colonies & main city |

Type & date of settlement |

Representative & Responsible Government |

NEW SOUTH WALES (Sydney) |

Penal settlement in 1788; Abolition of convict transportation in 1840; Responsible Govt in 1855 |

|

VAN DIEMEN’S LAND: renamed in 1856 TASMANIA (Port Arthur) |

Penal settlement in 1822 |

|

WESTERN AUSTRALIA (Swan River/Perth)

|

Started as a Free settlement colony in 1829 but due to economic problems brought convicts from 1850 to 1868 |

|

QUEENSLAND (Moreton Bay / Brisbane) |

Penal colony in 1825 |

Separate colony from NSW & Responsible Gvt in 1859 |

VICTORIA (Port Phillip/Melbourne) |

Free settlement colony in 1835 |

Representative Gvt in 1850; Responsible Gvt in 1855 |

SOUTH AUSTRALIA (Adelaide) |

Free settlement colony in 1836 |

Representative Gvt in 1850; Responsible Gvt in 1856; Northern Territory taken over by S.A in 1863 |

As the table shows, most colonies attained responsible government in the 1850s. This was mainly due to their economic independence achieved through the discovery of gold and the development of the wool industry. The basic requirement for self-government was the abolition of convict transportation. Western Australia, being the last colony to abolish transportation (1869) was consequently the last to attain self-government (1890). The colonies were, at last, on an equal footing and could therefore begin to entertain the prospect of Federation.

Federation (1901)

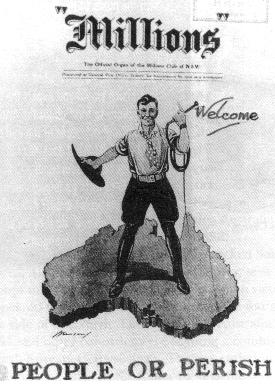

The movement towards political unity started in the 1880s but was slow to develop. Despite their differences, federation was considered desirable because of population growth, economic expansion as well as a perceived need for a unified defence and immigration policy.

At the closing of the last decade of the nineteenth century the "Yellow Peril"55 was viewed with real fear because of the expected mass-immigration of Asian workers after the gold rushes of the 1850s (which, it was feared, would inevitably lower the standard of living enjoyed by the average Australian worker as they would be forced to accept low wages) coupled with the menacing Japanese army the successes of which against China in 1895 were regarded as another warning that Australia should be prepared.

Henry Parkes of New South Wales (nicknamed the Father of Federation) was a fervent advocate of the establishment of a federal council to deal with certain matters of common interest to the colonies. In a speech he delivered at Tenterfield in 1889, Parkes proclaimed his belief that the whole of the forces should be amalgamated into one great federal army. To achieve this a system of federal government was required. Parkes went further on in his vision of what federation would mean for Australia:

...all great national questions of magnitude affecting the welfare of the colonies would be disposed of by a fully authorized constitutional authority, which would be the only one which could give a distinct executive and a distinct parliamentary power, a government for the whole of Australia, and it meant a Parliament of two houses, a house of commons and a senate, which would legislate on all great subjects. The Governments and Parliament of New South Wales would be just as effective as now in all local matters, and so would be the Government and Parliament of Queensland.56

The convention met in 1891 and Sir Samuel Griffith drafted a proposed constitution in which the colonies were expected to cede certain specific powers to a new central government, the chief of these being defence. It was argued that there should be free trade between the colonies though the question of a national tariff was not raised. The proposed bill also attempted to calm the fears of the smaller colonies such as Tasmania or South Australia, by calling for the creation of two Houses. The House of Representatives elected on a population basis and a Senate in which each colony would be equally represented.

The members of the conference were elected representatives. The convention of 10 delegates met for the first time in Adelaide in 1897. Griffith's draft bill of 1891 was used as the basis of discussions. The Bill was put to referendum in all the colonies and all voted in favour.

On 1 January 1901, the six colonies joined in a federation of states to become the Commonwealth of Australia. Australia as a nation was at last created. The Constitution, which gave form to this union was passed as a British Act of Parliament almost without modification, only six months before its celebration in 1901.

By federating, colonists acknowledged that they had more in common than differences from one another, a common language, a common ancestry as well as a growing sense of a shared Australian experience. But one of the main reasons behind federation was the determination of white Anglo-Saxon Australia to unite against a possible Asian invasion. The geographical position of Australia near Asia made Australia feel vulnerable as millions of Asians were at the door of the young nation of only 3,765,300 57.

White Australia Policy (1901-1970)

In the closing decades of the nineteenth century, racial homogeneity had become a major issue, with legislators strongly urging that the newly emerging nation must become a white man's bastion. Although racism towards non-British had always been a reality in the Australian colonies58, the White Australia Policy institutionalized it for the first time.

Many Australians, who believed that the white race was superior, wanted to make sure that the only people who came to settle in Australia were white people. Two of the first acts, unofficially known as the White Australia Policy, passed by the new federal parliament in 1901 were laws which restricted immigration of non-whites into Australia. Under this law the insane, anyone likely to become a charge upon the public, any person suffering from an infectious or contagious disease, prostitutes and criminals were also refused entry into Australia.

Blatant racism was commonplace in colonial Australia particularly towards the Chinese migrants of the Victorian gold-fields and the Kanakas (Pacific islanders) of the northern Queensland canefields. Non-white labor would, it was thought, work for lower wages and consequently threaten the standard of living of white Australia.

The 1901 Alien-Immigration Restriction Act was the first act passed by the newly formed Commonwealth of Australia. The basic vehicle of the restriction was a language test. The Act (clause (a), Section 3) prohibited entry into Australia of:

any person, who when asked to do so by an officer, fails to write out at dictation and sign in the presence of an officer, a passage of fifty words in a European language59

The customs officials could ask any would-be immigrants to be able to write a text in French or German or even Gaelic. If the applicant failed, he/she had no right of admission. This method became the principal means of enforcing a policy designed to control the sources from which the immigrants would be accepted. Being flexible, it could be used against anyone whom the government wished to exclude. Britain as well as Japan strongly protested against the uses of such practices but Australia, nonetheless, maintained the dictation test until the 1950s.

'T'aint their colour we object to, 'tis their spelling' [sic].

Cartoon from The Bulletin

in 1901.

This attitude was supported by most Australians as reflected by the statements of prominent elected politicians who were in favor of such restrictions. The following comments demonstrate the popularity of this attitude:

...if this young nation is to maintain its liberties it cannot admit into its population any element of an inferior nature.60

There is no racial equality. There is that basic inequality. These races are, in comparison with white races, unequal and inferior.61

We should be one people and remain one people without the admixture of other races...They do not and cannot blend with us, we do not, cannot and ought not to blend with them.62

Our chief plank is, of course, white Australia. There is no compromise about that. The industrious coloured brother has to go - and remain away.63

The newspapers were also very clear in their support for a White Australia, particularly The Bulletin64 which had until 1961 as its masthead Australia for the White Man.

If Australia is to be a country fit for our children and their children to live in we must KEEP THE BREED PURE. The half caste usually inherits the vices of both races and the virtues of neither. Do you want Australia to be a community of mongrels?65

The little brown men came leaping over our... borders by scores and hundreds... And wherever they go the destruction of industry follows in its train.66

The policy of this country is to elevate labour as much as possible and we cannot , therefore, wish its degradation by the free admission of workmen who are content to labour for a handful of rice and the most wretched shelter. 67

The constant emphasis on keeping the breed pure was related to the world-wide movement of eugenics "a science which deals with all influences that improve the inborn qualities"68.

This so-called science was used69 to support claims that by improving their genetic inheritance by the selection of the population through birth control or immigrants' intake, they were working for the benefit of humanity.

In the aftermath of the introduction of the White Australia Policy, immigration into Australia was encouraged mainly from one source: Great Britain. The result was an overwhelming number of people in the Australian population who were either of British origin or Australian-born with a British cultural background. Special schemes were designed to offer assistance with passage, costs taken care of and governments helping with accommodation and jobs on arrival.

With the threat of the "Yellow peril" still present, assisted migration to Australia from the United Kingdom was encouraged between 1905 and 1914.

The effect of this selective immigration was that by 1947 Australia's population had more than doubled with more than 90 per cent (90.2%) of that population being of British descent. Australia, by selecting its migrants, had ensured a racially homogeneous society (see figures below).

Year |

Anglo-Saxon population |

Percentage |

1891 |

3,280,000 |

87.2% |

1947 |

7,709,000 |

90.2% |

1978 |

14,263,000 |

76.9% |

In fact, from the time Europeans settled in Australia in 1788, immigration has been a key element of Australian history. Over the 209 year period 1788-1997, the population grew from an estimated 300,000 to 600,000 Aborigines to some 18,000,000 persons of many different ethnic origins - 65 per cent by natural increase and 35 per cent by immigration.

At the end of the Second World War, the Australian government was encouraged to accept northern and southern Europeans as suitable immigrants. The famous cry of Arthur Calwell, the then Minister for Immigration, Populate or Perish, was not the beginning of a conscious multiculturalism. Rather, it was Calwell reacting to the old threat of the "Yellow Peril". Calwell pushed for new Europeans as British migrants were not coming in sufficient numbers.

In the Cold War context, what mattered was not so much racial purity but the preservation of a certain standard of living and social rights which were threatened by Russian expansionism. The phobia of a possible spread of communist ideals through the growing strength of the Australian Communist Party and of intellectual dissidents prompted the Institute of Public Affairs to insert a full-page newspaper advertisement in 1949 to warn the general public of communist propaganda in Australia :

It is the communist influence within the Labour Party that is lowering production. This dangerous influence must be eradicated if the Australian way of life is to survive.70

Immigration in Australia had not been steady. In times of economic boom, like the Gold rushes of the 1850s or the post WW2 period, Australia welcomed huge numbers of immigrants whereas during recession periods such as the 1890s, 1930s or in periods of war, Australia's immigration policy changed overnight by closing its borders. This phenomenon is in no way specific to Australia but the percentage71 difference is very noticable causing many people to compare Australia to a boa-constrictor

... taking huge gulps of immigrants when times are good, or when gold, copper, oil and other minerals are discovered, and then quieting down for digestion during periods of war and recession.72

Notions of immigration policy were, until recently, ethnically restricted. The insistence on racial sameness was considered essential to the building of a common culture of shared values. The geographical position of Australia, south of Asia and its hundred of millions of inhabitants was also an important factor in encouraging the development of a "white nation"73.

The main stress was on development and population growth, or on what has been more recently termed "national need". Healthy, young and able immigrants were given financial assistance for passage and on arrival. Family reunion and refugee claims did not become an issue until the mid-1970s.

By the 1980s the Australian population was no longer dominated by the Anglo-Saxon. The introduction of a multicultural immigration policy in the 1970s drastically altered the ratio of Anglo-Saxons to non-Anglo-Saxons in the Australian population.

Bicentenary Controversy (1988)

1901 and 1988 are key dates in Australian history. 1901 saw the Commonwealth of Australia coming int existence and 1988 was the bicentenary year of the colony of New South Wales.

The complete reversal in migration policy by 1988 and improved conditions for minorities seemed to demonstrate that Australia had become mature enough to deal with change and diversity within its population. The old demons of "the yellow peril" and "the great Australian silence"74 seemed to be long gone as the Bicentenary approached. But further "tests" were yet to be passed as conflicts over what there was to celebrate became more and more heated.

The confusion was such that many Australians actually asked themselves during the 1980s whether Australia should celebrate 1988 at all. As a Sydney Morning Herald journalist pointed out:

What exactly is this "Australian-ness" we are supposed to be celebrating? What generalisation could you possibly make to the 15 million people who live on this continent? Or even most of them? [...] How are Aboriginals supposed to be included in what is basically a celebration of 200 years of white colonialism?75

History became a problem in 1988. The 1988 celebrations - the Celebration of a Nation - neither commemorated the whole of territorial Australia (being only the anniversary of the founding of the colony of New South Wales) nor did they celebrate the founding of the politico-administrative Australia (Australia was not established until 1901 and even then with the exclusion of its indigenous inhabitants from the right of citizenship).

Furthermore, cultural diversity meant that Australians were forced again to reassess what it was that Australia should stand for. An unequivocal celebration of 200 years of Anglo-Saxon achievement was politically as well as morally unacceptable. Malcolm Fraser, Prime Minister of Australia from 1975 to 1983, saw the celebration in the context of national cohesion, the need of a community for consciousness of its origins. Fraser, then, saw the Bicentennial as an affirmation of the importance of tradition and continuity in a sound community. He did not acknowledge the growing population diversity which had started with the mass post WWII immigration and the arrival of Vietnamese and Cambodian boat people as being important to Australia's future.

Bill Hayden (then the leader of the Federal Opposition) announced his support for the celebration but went a bit further by stressing the need for an exploration of what he called the distinctive Australian character:

There is a distinctive Australian character. I believe it developed from the need of our pioneers to come to terms with an environment totally unlike any they had ever known. This land has moulded the national character into a style and a resilience all of us recognize, though few are able to express it satisfactorily.76

Then, adding a new confusion to the already blurred notion of what Australia should celebrate, the Prime Minister outlined in 1979 what the Bicentenary "should be like":

It will be a time to reflect upon our developing and changing national identity, as a united community transformed in a remarkable way by the migration programs of the years since World War II.77

The Bicentenary was then the beginning of yet another attempt at self-definition. The Australian Bicentennial Authority (ABA) set a number of objectives concerning the celebration of the new Multicultural Australian society, such as:

To celebrate the richness of diversity of Australians, their traditions and the freedom which they enjoy. To encourage all Australians to understand and preserve their heritage, recognize the multicultural nature of modern Australia, and look to the future with confidence. To ensure that all Australians participate in, or have access to, the activities of 1988, so that the Bicentenary will be a truly national programme in both character and geographic spread.78

Unlike the celebrations of 1888 and 1938, the Bicentenary of European occupation did not pretend that convicts had never existed. By 1988 some Australians saw convict suffering, resistance and achievements as a more appropriate legend than that of the Anzacs. The convict stain no longer embarrassed direct descendants, or even Australia as a nation. Yet, the command to Celebrate 88 was as selective about the events that Australians were encouraged to remember as previous official programs had been. Recognition of an Aboriginal history of Australia was beginning to become more and more apparent. While the official celebrations ignored the unpleasant facts of two hundred years of conflict and dispossession, the sight of the frequently seen graffiti, White Australia has a black historyin 1988, emphasized the struggle of the Aborigines to put into perspective the need for a reassessment of Australia's history. The arrival of tall ships in Sydney on the morning of 26 January 1988, for the reenactment of the first fleet's arrival, was answered in the afternoon by a mass march and rally of Aborigines and their supporters. Novelist Thomas Keneally said on this occasion:

Let's drink to pre-Australia, its mysteries, its glories, and even its demands. Until we've both imagined and dealt with it, we'll never be fully at home.79

The major problem for the ABA was how to deal with the Aboriginal question. Too much emphasis on the First Fleet was clearly divisive while downplaying the significance of the First Fleet automatically posed the question, "Why pick 1988 in the first place?" According to the ABA's journal Bicentenary

...the Bicentenary in 1988 represents much more than the anniversary of this event. The Bicentenary celebrates all the people who have settled in this land over many thousands of years...80

The different Governments preparing the Bicentenary wished to make peace with the indigenous Australians but how could the Aborigines be expected to view 200 years of colonisation and dispossession as anything other than an insult! The Bicentenary not only awakened Aboriginal pride, it also gave them the perfect platform from which to air their political and social grievances.

The Aborigines took the opportunity of the "celebration of a nation" to make their version of Australian history known. Excerpts from the speeches given at a protest rally were edited and published in Paperback : A Collection of Black Australians Writings81. Aboriginal speakers questioned some of the principal non-Aboriginal concepts at the center of the Bicentenary celebration and presented opposing Aboriginal perspectives. These "opposing pairs" were:

The Aboriginal people's perspective of Australia Day 1988

("Invasion Day"), La Perouse, Sydney.

This Aboriginal perspective of the meaning of the Bicentenary seriously challenged conventional, established Australian history. It led to a whole series of books and films which started to have an impact on the way Australians saw themselves and their national history. Film, as a powerful popular medium, had a major role in presenting this challenging new perspective. Documentaries like Lousy Little Sixpence, the television series Women of the Sun and the works of Aboriginal film-maker, Tracey Moffat (e.g. Nice Coloured Girl and Night Cries) were decisive in shaping a new national history incorporating the Aboriginal experience.

In the film Babakuiera (1988), the Bicentennial view of Australian history is turned around by placing non-Aboriginal people in the Aboriginal position. A group of Aborigines in uniform land in a new country. They ask locals what this place is called and are told Babaquiera(which stands for BBQ Area). This is a parody of the landing at Botany Bay, which the British "invaders" felt gave them the right to the land. The film continues with the interview of a white family by an Aboriginal journalist. Among the themes discussed are the removal by force of children, the frequent arrests and deaths in custody, as well as the paternalistic attitude of the journalist who grows attached to "those peculiar but nice people". This kind of film provided a strong incentive for the "white invaders" to question the so-called "official" version of Australian history.

Politicians had feared the problems that might flow from the celebration of "200 years of invasion". Fear of violent demonstrations soon gave way to respect when the demonstrations turned out to be peaceful. The biggest and most important demonstration was the "March for Freedom, Justice and Peace" which took place in Sydney (from Redfern Oval to Belmore Park) on the afternoon of January 26th - Australian Day.

The march made a slow but peaceful progress, even stopping to allow a car to drive past. But as it edged closer to the city and as white Australians stood on the footpath to cheer them on, the atmosphere became electric. Soon after the thousands of white supporters had joined the march at Sydney's Belmore park, one white woman sat down and wept. Black and white Australians hugged each other and others cheered and whistled...82

The protest marches organised throughout 1988 (in Sydney and Canberra in particular) were events which brought black and white Australians together and transformed a celebration of the past into a brighter hope for the future.

The Bicentenary became a springboard for the Aboriginal cause and accelerated the process of reconciliation. As the academic Graeme Turner suggests,

I would not be the first to suggest that the most

"unintended consequence" of the Bicentenary was the elevation of Aboriginal

rights in the national consciousness of social policy imperative.83

So as to avoid putting too much emphasis on the British colonization

of Australia, the official reconstruction of the celebration shifted from the voyage

of the First Fleet, to all the voyages of arrival and to all the people who

settled in Australia. The first arrivals (the Aborigines) as well as the

recent arrivals (from Asia and other countries) were included. The distinction

between the older (indigenous) and newer arrivals was blurred. It was hoped that every Australian would sense a shared identity

made equal by their shared "immigrant" status. This strategy also allowed the

celebration of the multicultural nature of contemporary Australian society.

[It may be argued that this was another demonstration of the Australian egalitarian

leveling effect at work. Putting indigenous people on the same

level as more recent arrivals had the effect of weakening Aboriginal claims to land.] David Armstrong, the then general manager of the ABA, was the first to

stress this new view of the "Journey" by telling the press that the celebration

was as much about 40,000 years of the Aborigine and the four

weeks of the Vietnamese boat people as it is about 200 years of the British and their

descendants.84

The Bicentennial celebration was an occasion for many white

Australians to rejoice. It was also viewed as a decisive force in shaping the image of

Australia overseas. A "politically correct" handling of the celebration was considered important

as the tourist industry in Australia was becoming a major source of income. To this effect,

a Press Kit was produced and handed to foreign tourists to explain what the celebration

was all about: Is this Exhibition merely an expression of 200 years of

European settlement? No, it includes Aboriginal beginnings, aspirations and contributions

to Australia. It also includes the contributions made by the various migrant communities

to their new homeland.

The controversy surrounding the Bicentenary demonstrates the difficulty Australia has (perhaps all "young nations" have) in self-definition. Were Australians the descendants of the convicts, the bush man, the Anzac soldiers, or of a multitude of nations? 1988 (and the years since) has seen a growing acceptance by a majority of Australia's Anglo-Saxon population of a more plural image of the Australian type. This was reflected, for example, in the different pavilions 85 of the 1988 World exhibition in Brisbane 86, Queensland. The Bicentenary organizers and their critics helped in a positive re-evaluation of Australian history as well as in a major shift towards a more truely egalitarian Australian society that would include every Australian.

Notes13 Ward, Russel. The Australian Legend.OUP Australia (Vic). First edition 1958. Second edition 1966.

14 Bushrangers, such as Ned Kelly or Captain Thunderbolt, were mostly convicts who escaped in the Bush and organized themselves in gangs. They managed to survive in the Bush reputedly robbing only the rich (a kind of Australian version of Robin Hood)

15 Bush with a capital "B" was first introduced by Henry Lawson in the mid-1890's. It was I, who insisted on the capital B for Bush Lawson to G. Robertson, 21 January 1917 as quoted in Colin Roderick (ed.), Henry Lawson, Collected Verse, vol. 1, 1885-1950, Angus and Robertson, Sydney, 1967. p. 423.

16 Ward, Russel, Foreword to the 1958 edition of The Australian Legend, OUP

17 Ward, Russel, Foreword to the 1966 edition of The Australian Legend, OUP

18 Ibid. p. 1. 1958 edition.

19 Ibid. pp. 1-2. 1958 edition.

20 See mateship in Part 1

21 See Federation in details in Part 1

22 Ward, Russel Op. Cit. p. 15. 1966 edition.

23 Hughes, Robert The Fatal Shore, A History of Transportation of Convicts to Australia, 1787-7868. First published in 1987 by Collins Harvill. 1996 Paperback edition by the Harvill Press, London. Introduction pxi

24 In December 1854, the miners of Ballarat gold-fields suffered under the harsh control of the troopers, and the oppressive regime of Governor Hotham. They considered that life on the gold-fields was rough enough without having to pay high fees for the right to dig. At a protest meeting at Bakery Hill, above the town of Ballarat, 500 miners took an oath to fight for their rights and liberties. They decided to make a stand at a place called Eureka Lead. It was there they built their stockade and ran up their new Southern Cross flag. The next day the miners defied the police and burnt their licenses. This led to a shoot-out in which twenty-two diggers and six soldiers were killed. All in all, the battle only lasted about fifteen minutes. Eureka and the Southern Cross flag have become symbols for the Republican Movement.

25 Manhood Suffrage was introduced in South Australia as early as 1855, the other colonies following closely (Victoria, 1857 and N.S.W , 1858), more than ten years before England or Canada.

26 The Secret Ballot was first adopted by South Australia and Victoria in 1856, was dubbed "kangaroo voting" and is still known as the "Australian Ballot".

27 South Australia gave the franchise to women in 1894, more than twenty years before England or Canada, while Australia became the second national system (after New Zealand) to adopt this reform.

28 Trade unions as wells as humanitarian and women associations.

29 ANZAC - Australian and New Zealand Army Corps

30 Turner Ian. Room for Manoeuvre. Drummond Book, Richmond (Vic). 1985 p. 14

31 Ward, Russel, The Australian Legend. 1966 edition. OUP. p. 99.

32 C.W.E Bean in The Sydney Morning Herald (1907). Quoted in The Australian Legend, Ibid.

33 Thompson, Elaine, Fair Enough, Egalitarianism in Australia. UNSW Press. 1994. p. 134.

34 Ward, Russel, Finding Australia, The History of Australia from 1788 to 1821. Heinemann, Richmond. 1987. p 397.

35 Squatters are landowners who took huge areas of land to run huge flocks of sheep.

36 Ward, Russel, The Australian Legend. 1966 edition. OUP. p. 95.

37 For example, the Eight-hour day campaign led by unions (such as the Operative Stonemason's Society) in 1856. Eight-Hour Day meant "8 hours to work, 8 hours to play, 8 hours to sleep, and 8 bob a day" as seen in A Time to Remember by Peter Luck, Heinemann Australia. 1988. P.67.

38 Hughes, Robert, The Fatal Shore, Introduction The Harvill Press, London. 1987. P. xii.

39 See Federation of the Australian colonies as States

40 Henry Lawson, quoted in Questions and Issues in Australian History. Merritt Alan O'Brien Carolyn, Nelson Education Australia, South Melbourne (Vic). 1995. p. 274.

41 As quoted in Australian Civilisation . Chapter 3, Myth by Bruce Bennett. OUP. 1994 p. 58

42 Bean C.E.W The Official History of Australia in the war of 1914-1918, !2 Vols. Angus and Robertson, Sydney (NSW). 1938-1942. As Quoted in A Time to Remember, Peter Luck's Bicentennial Minutes William Heinemann Australia. 1988. p. 195.

43 Nigel, Adnum in The Bulletin April 27, 1993 "Forever Anzacs" Special Report. Back to Gal1ipoli p. 41

4"Mostly poor people who lived in debauchery, filth and violence and who stole food or money in order to survive with their family."

45 Hughes, Robert The Fatal Shore London Pan Books, 1987

46 Punishments for convicts were still severe. There were about 12 hangings per year, flogging was continued and solitary confinement on bread and water was common, as was time in chain gangs. As seen in Dreamtime to Nation, edited by Lawrence, Eshuys, Guest MacMillan, Melbourne. 1991. p. 150.

47 Free settlers arrived in NSW as soon as 1810 and numbered 2000 out of 30,000 convicts by the time Macquarie left the colony in 1821

48 In 1810, 90% in the NSW colony were either convicts of children of convicts.

49 If introduced in 1797, the first shipment of salable wool to England did not occur before 1807.

50 By 1850, Australia exported a total of 18 million kg of wool to Great Britain (seen in Dreamtime to Nation op cit. p. 168)

51 Plantation societies made a living by cultivating sugar, tobacco or cotton. They required a large cheap labour force which was supplied easily by the penal colonies.

52 For further details later reading

53 going from an estimated 300,000 in 1788 to a mere 22,200 in 1860, as seen in The Little Aussie Fact Book by Margaret Nicholson. Penguin Book. First published in 1985, this edition 1995. P. 57.

56 Self-government meant the right of the colonies to rule themselves, except for foreign affairs, which was still controlled by Britain.

57 Representative Government meant that the people had the right to elect a person to represent them in English parliament. Responsible Government meant that the governing party and its ministers were responsible of the parliament while the parliament was responsible of the people.

58 "Yellow Peril" was the common expression which referred to the threat of a mass-Asian immigration to Australia.

59 Henry Parkes' Tenterfield address. 1889, quoted in Barnard Marjorie’s A History of Australia. Angus & Robertson. Sydney. 1962. p. 453.

60 As seen in Margaret Nicholson's The Little Aussie Fact Book. Op. Cit. p. 57

61 beginning with the first contact with the Aborigines and continuing with the arrival of the Chinese into the goldfields of Victoria during the 1850s and the Kanaka labor in the canefields of Queensland in the 1880s.

62 Quoted in Australia, A Land of Immigrants by Beryl and Michael Cigler. The Jacaranda Press, Milton (Qnd). 1985. p. 130.

63 Parkes Henry, the "Father of Federation" quoted in Australia Emerges Joe Eshuys, Vic Guest and Judith Lawrence. MacMillan Australia, South Melbourne (Vic). 1995. p. 20.

64 Edmund Barton, first Prime Minister of Australia (1901-1903),. Ibid.

65 Alfred Deakin, later to become Prime Minister of Australia, (1903-1904 & 1905-1908), Quoted in Australia Emerges. Joe Eshues, Vic Guest and Judith Lawrence. MacMillan Australia . 1995. p. 20.

66 William Morris Hughes, Prime Minister of Australia (1915-1922) Ibid.

67 The Bulletin, whereas a socialist oriented newspaper, was the principal medium of nationalists writers such as Henry Lawson and Banjo Patterson who wrote abundantly on the Bush between 1890s-1910s.

68 The Bulletin 31 August 1895

69 The Bulletin. January 1901.

70 The Age 30 May 1887.

71 Eugenics definition as found in the Cambridge Paperback Encyclopedia. Edited by David Crystal. CUP. 1993. pp. 259-260.

72 German Nazis in the 1930s-1940s and in a lesser way Australia through its immigration policy (1900-70s)

73 Institute of Public Affairs, Report on the Activities of the I.P.A, Sydney, 1949.

74 See Figure 1. as seen in Australian Multicultural Society, Identity, Communication, Decision-Making. Edited by Donald J.Phillips and Jim Houston. Drummond Book. 1984. p. 10.

75 Charles Price in Op. Cit. p. 7.

76 See also Yellow Peril footnote 58

77 the great Australian silence is an expression first used by Australian anthropologist, W.E.H Stanner at the 1968 Boyer Lecture, it refers to the absence of the Aborigines from Australian history written between 1890 and 1970s. See in details in 4.1

78 Craig McGregor, Sydney Morning Herald, (edited version), 7 October 1985.

79 In Celebrating the Nation, A Critical Study of Australia’s Bicentenary. Edited by Tony Bennett, Pat Buckridge, David Carter and Colin Mercer. Allen & Unwin. 1992. p. 177

80 Fraser Malcolm in Celebrating the Nation, A critical Study of Australia's Bicentenary. Edited by Tony Bennett, Pat Buckridge, David Carter and Colin Mercer. Allen & Unwin, Australian Cultural Studies series. 1992. Part 2. Representations and Lineages. Chapter 6. P. 113

81 Australian Bicentennial Authority. How to Make it Your Bicentenary. 1987.

82 Thomas Keneally in The Age, 1 January 1988.

83 National Programme, Bicentenary Special Issue, 1985. p. 1.84 Paperback : A Collection of Black Australians Writings. Davis et al., 1990.

85 Annette Young, "Veterans of black struggle take to Sydney streets" The Age., 27th January 1988.

86 Graeme Turner, Making it Nation al, Nationalism and popular culture. Allen Unwin. P. 87.

87 Malcolm Andrews, Bicentenary group hopes to lock up the tourists. The Australian. 08/25/1980. p. 9.

88 The World Expo at Brisbane in 1988 showed several pavilions depicting each state and their mixed population and even more importantly an Aboriginal pavilion acknowledging in full the presence, the contribution and the importance of the native population of Australia.

89 The Brisbane World Expo, despite being an international venture, was a flop if one considers that 70% of its attendance consisted of Brisbane residents.