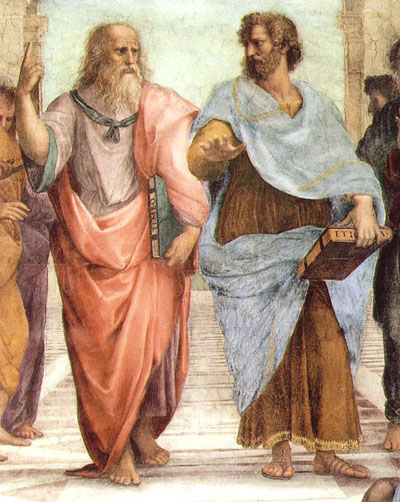

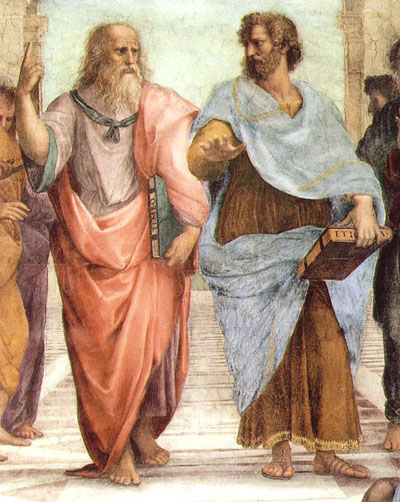

Raphael, "School of Athens" (Detail of Plato & Aristotle) 1511

Vatican Palace, Rome

platonism

Raphael, "School of Athens" (Detail of Plato & Aristotle) 1511

Vatican Palace, Rome

The philosopher Plato (left above with his student Aristotle) did not write

views under his own name (his writings are mainly in the form of conversations called 'Dialogues',

between Socrates and other Greek philosophers of

the fifth century B.C.). Nevertheless certain

views are attributed to Plato as being his own.

Many classical theories assume that if we know what good is we will naturally act to try to achieve it.

If we can discover what is right, Plato believes, we will never act wickedly. Evil is due to lack of knowledge.

Do you think this is true? Give reasons for your answer.

But the problem is to discover what is right, or as Plato

called it, 'the good'. How can this be done when we

differ so greatly in our opinions about the good life?

Plato's answer is that finding the nature of the good

life is an intellectual task similar to the discovery

of mathematical truths. Just as the latter cannot be

discovered by untrained people, so the former

cannot be either.

In order to discover what the good life is we must first

acquire certain kinds of knowledge. Such knowledge can

be arrived at only if we are carefully schooled in

various disciplines, such as mathematics, philosophy,

and so on. Only when we have been through the long

period of intellectual training that Plato suggested,

would we have the capacity to know the nature of

the good life.

lt is important for an understanding of Plato to make

a distinction at this point. Plato did not maintain that

we must have knowledge in order to lead the good life.

He maintained the weaker doctrine that if we

did have knowledge we would lead the good life.

Even without the possession of knowledge it is

possible for some people to lead the good life,

but they will do so haphazardly or blindly.

It is only if we have knowledge that we can be

assured of leading such an existence.

This is why Plato believed that we must be instructed in

two different ways. We must develop, on the one hand,

virtuous habits of behaviour, and on the other,

we must develop our mental powers through the

study of such disciplines as mathematics and

philosophy. Both of these types of instruction are

necessary.

First, some of us may not have the intellectual

capacity to get knowledge. But if we are guided by

those people who have knowledge of the good, and who

accordingly act virtuously, we, too, will act virtuously

even though we do not understand the essential nature

of the good life.

On the basis of this sort of reasoning, Plato went on to

advocate the neccssity of censorship in what he called an

'ideal society' - the society which is portrayed in his

famous book, The Republic.

Plato felt that it was

necessary to prevent young people from being exposed to

certain sorts of experiences if they were to develop

virtuous habits & thus lead the good life. Secondly,

it was necessary for some people to

develop their mental powers & undergo

rigorous intellectual training which will do more than develop virtuous habits.

These exceptional people, Plato thought, must finally be the rulers of

the ideal society. In such a society, the rulers, having

developed their intellectual capacities, would also

have acquired knowledge. And having acquired knowledge

they would understand the nature of the good life.

This would guarantee their acting rightly or morally,

& hence would ensure their being good rulers. For,

as we have seen, it was Plato's belief that if we can

acquire knowledge, in particular knowledge of what

was good, then we would never act evilly.

A second basic element in Plato's philosophy is

what modern scholars term his "absolutism".

According to Plato, there is fundamentally one

& only one good life for all people to lead.

This is because goodness is something which is

not dependent upon people's inclinations, desires,

wishes, or upon their opinions. Goodness in this

respect resembles the mathematical truth that

two plus two equal four. This is a truth which is

absolute; it exists whether anyone likes such a

fact or not, or even whether s/he knows mathematics

or not. It is not dependent upon our opinions

about the nature of mathematics or the world.

This can be put in another way. Plato is arguing

for the objectivity of moral principles as opposed

to other philosophies which contend that morality is

merely a "matter of opinion" or "preference". It is

an absolute]y objective moral law that "Thou Shalt

Not Commit Murder".

Platonism had a tremendous impact upon religious

philosophy. Most theologians believ that

moral laws such as "Thou Shalt Not Steal", or "Thou

Shalt Not Commit Murder" are absolute & objective

in the Platonic sense.

The development of Plato's philosophy (known as

Neo-Platonism) was the nearest Greek philosophy came

to itself becoming religion & had a direct influence

on the development of Christian theology. But it should

be pointed out that although Platonism & most theologies

agree in contending that moral standards are objective,

there is a basic difference between them. Plato himself

believed that moral standards were superior even to God,

& God is good if & only if s/he acts in accordance with

such a standard. This is very different from the

Judaeo-Christian view that God creates goodness.

criticisms of platonism

As we have seen, Platonism as a moral philosophy rests

upon two basic assumptions. One is the assumption that

if a man has knowledge of the good life, he will never knowingly act

immorally. The other is that there is one & only one good

life for all humans; just as there is no moral alternative to

the command: "Thou Shalt Not Steal".

Most philosophers who criticize Plato have interpreted this

as expressing a psychological judgment about how we act

under certain conditions. The conditions are that if we have

a certain kind of knowledge, we will behave in a certain way.

Interpreted as a psychological account of how we behave

in every case, the theory seems to have problems. For

some of us may well understand that stealing is wrong

(for example) but we may still persist in stealing.

Plato would say of such people that they really do not

understand what is meant by "stealing" since no-one

willingly will do what they know to be wrong. But if we

talk to such people & if they give the usual signs of

understanding what it means to steal, and further,

if they admit it to be morally wrong but still steal,

it appears as if Plato's account must be rejected, since

it seems that some of us will act wrongly while knowing

what the right course of action is. This was the view

of human nature taken by Aristotle.

But what makes Plato's account attractive is that it

attempts to supply a general solution to a common type

of difficulty which arises in daily life. We often find

ourselves in situations where we do not know how to

behave because we do not know what the right course

of action would be in those circumstances. Is it right

to defend my country if this means killing someone,

or is it right never to kill anyone?

What Plato suggests is that if we had more information,

if we had been more carefully trained, we could discover

the answer. We would know what the right course of action

would be in those circumstances & thus our perplexity

would be relieved. The situation seems analogous to many

problems which a doctor faces: Should he operate now or

wait until tomorrow? Should he administer this drug or

not? These are problems which would be hopelessly difficult

to the average person since s/he does not have the training

& hence the knowledge to solve them. But to a trained

person, the difficulty is reduced or overcome.

Plato's point is that moral difficulties are often

theoretically solvable by the gaining of further knowledge -

and this is a point of view which cannot be lightly dismissed.

The major objection to it, however, is this. Moral problems

are not the same as scientific questions. When all the relevant

facts have been gathered in a scientific issue, we can in

principle always decide the issue. But this is not so in a moral

situation. We may know all the relevant facts in a given situation.

We may know, for instance, that the effect of dropping a bomb on

a certain area will be to kill 1,000 people, and, on the other hand,

we may also know that if we drop the bomb, a disastrous war will

be shortened. But our perplexity still exists. Should we or should

we not drop the bomb? Although the acquisition of further

information about a situation will solve some difficulties we have

about acting in that situation, this is not always so. Platonism

cannot be accepted without considerable qualification. Moral

knowledge is not analogous to scientific or mathematical

knowledge & Plato's mistake was to think that it is.

A further criticism that arises from this is that, since Plato

regards morality as being a matter of knowledge, he almost

excludes the possibility of fully moral behaviour for all but a

few intellectually gifted people. It is not sufficient to say that

those of us who do not have this ability can live good lives by

allowing ourselves to be ruled by those who have,

since to behave morally presupposes that one has responsibility

for one's actions. An action is not truly moral (or immoral) unless

it is the result of the free choice of the individual performing it.

To make this choice the individual needs the kind of moral

understanding that Plato says is possible only for a few.

Again, we shall find Aristotle shows a clearer awareness

of this basic feature of moral behaviour than Plato.

The second basic assumption of Platonism is that there is one

and only one right course of action for all people - this is

his "absolutism". Even in ancient times this view was strongly

criticized, again by Plato's greatest pupil,

Aristotle. Aristotle's moral philosophy rejects Platonic

ideas that there is one & only one right course of action

in a given moral situation, that good behaviour is not possible

without moral understanding, and that knowledge of the

good will necessarily lead to virtuous behaviour.